A New View

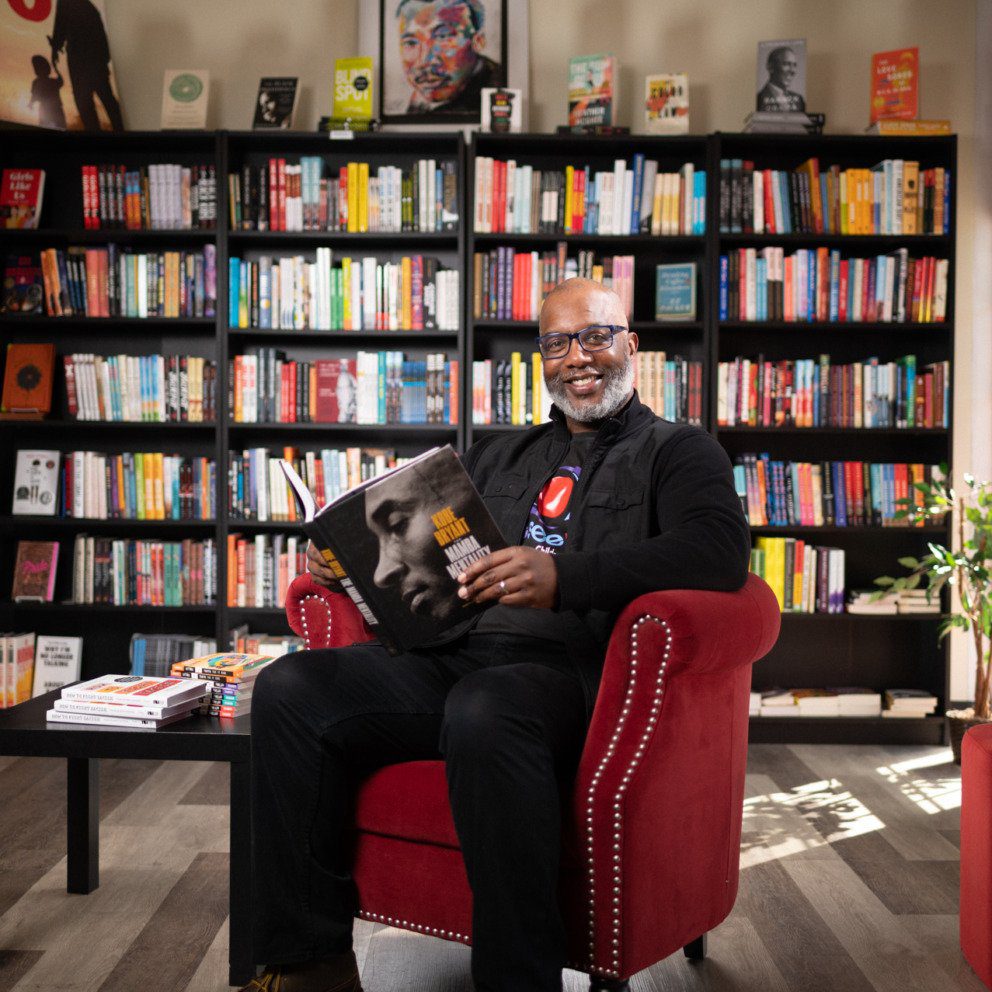

As president and CEO of the Missouri Historical Society, Jody Sowell focuses on telling stories about St. Louis’ past that ignite civic passion for how the city can evolve into the future.

Jody Sowell is a St. Louis transplant and former journalist who moved to the area to pursue a doctorate in American Studies at Saint Louis University, then promptly fell in love with the city and rooted his family here. Through his role as president and CEO of the Missouri Historical Society, he is now spreading his enthusiasm with the goal of introducing MHS visitors to “a St. Louis they’ve never met” via a slate of ambitious, creative projects that depict both the wonder and complexity of St. Louis history.

What makes St. Louis so distinctive, in your view?

St. Louis has a rich, diverse and complex history. There are so many fascinating stories to be told, and none of them are simple stories. They all have multiple layers. But also, you can tell just about any story of American history through St. Louis — whether it be westward expansion, architecture history, civil rights history or urban boom and bust and hoped for revitalization. You will understand the American story better if you hear those stories through the lens of St. Louis.

How does the focus of educating St. Louisans about the past shape our present and future?

It starts with place attachment. Research shows that only 24% of people say they feel connected to where they live. But the areas with the highest place attachment also have the highest local gross domestic product and even survive natural disasters at a higher rate. And people who live in those communities say they feel less lonely. So creating that attachment to place is key to tackling the problems in our community. That’s where we think the Missouri Historical Society has a role to play, because we can show you why this place is so special. And when we do, it will help create a stronger St. Louis for the future.

What are some of the upcoming changes at MHS that you are most excited about?

In the years and decades ahead, our promise is that we’re going to introduce you to a St. Louis you’ve never met. Opening in 2027, we will have a decade-by-decade walk-through that tells you the major story for every decade in addition to how life was lived during that time, from what people were eating to what it was like to go to a dentist.

We are creating a number of projects that spin off this idea. Starting this year, we are going to have a new-to-St. Louis program for corporations that have employees new to town. We will be the place to start connecting them to St. Louis. We also are going to create a Future STL Summit, where every year we bring thought leaders together to talk about an issue facing St. Louis today, whether it be crime, population loss, city-county divide or food deserts. We’ll provide the historical context and then ask people to discuss how we address these problems.

And we’re going to showcase more of our collection, digitizing much of it so people can explore from the touch of a button. So many things planned … mohistory.org/vision is where people can find the full list of projects.

How does the emphasis on civic engagement compare to other historical societies across the country?

I don’t think anyone is putting the focus on civic engagement to the extent that we are. I also don’t think many museums across the country are having as much fun with history as we are. We had a recent exhibit that told the story of one year in St. Louis through floor-to-ceiling cartoons. We had another where we created a 20-foot-long skyline of St. Louis made with coffee beans roasted at six different levels. We are a real leader in the country, which is something St. Louisans don’t always realize.

Talk about the renovation of the World’s Fair exhibit. How do you strike a balance between “reliving the wonder” while also “reexamining the complexity?”

The World’s Fair might be the best-known story in St. Louis history. But despite this, there are so many stories people don’t know. And people are hungry to hear those multiple layers. For example, we put people on display in a sort of human zoo with the Philippine village. That was one of the most popular facets of the fair, but it was part of a larger project of American imperialism.

The complexities don’t stop there. We also had baby incubators that were less of a scientific display and almost a sideshow. There was a recreation of the Boer War, which had just happened a few years before, with the actual real-life soldiers recreating the war for entertainment purposes.

Those are the types of complexities we will explore in this exhibit that people tell us they’re hungry for. And — I think this is important — you can talk about the complexities of history in welcoming and inviting ways, not in lecturing or scolding ways. That’s what people want.

Tell us about the digitization efforts at MHS.

Sure. Right now, less than 5% of our collection is digitized, which makes it hard for some people to use it. By the end of this decade, thanks to a lot of great support from the community, more than 20% of our collection will be digitized. More people will be able to see it online, but also educators will be able to use primary sources to engage their students in history. That may be what I’m most excited about.

Are there any areas of St. Louis history that you are particularly interested in?

I always say that every aspect of St. Louis history is interesting; you just have to find the right stories. I will add, we are working on an exhibit coming up in the next few years about The Ville neighborhood, which is one of the most historically important Black neighborhoods in the United States, not just in St. Louis. And yet I worry that not enough people know what we have here and how important it is to preserve the institutions we still have in that neighborhood. The Ville is home to Sumner High School, the oldest Black high school west of the Mississippi. It was the home of Homer G. Phillips Hospital, which at one point was training 50% of Black doctors across the country. It was home to Poro College, the beauty empire created by Annie Malone, one of the country’s first Black female millionaires. It’s such an important place and neighborhood. I’m looking forward to telling that story in the next few years.

What is your message to potential visitors to MHS?

What I love most about MHS is that it’s surprising. If your perceptions of history museums are that they are these stuffy, boring places, we quickly disabuse you of that idea. Whether it be going to Soldiers Memorial to learn about military history, or going to our research center and learning that you can discover the history of your own home, or learning about the history of popular American music through St. Louis … Or right now we have an architecture exhibit that literally allows you to color on the walls of the museum … We’re always looking for new ways to tell the story of St. Louis. I love nothing more than when people tell me, “Oh, I hate history,” because I can say, “No, it’s just been presented to you in the wrong way. I can prove that you actually love history when we make it compelling, engaging, meaningful and memorable.”

Join the Story

Learn more about the Missouri History Museum.