Sewing Hope

The Collective Thread's small-batch manufacturing company was hard-hit by the pandemic, but once they pivoted to making and selling cloth masks, the immigrants and refugees they employ were able to not just keep their jobs, but actually increase their incomes.

For Zohra Zaimi, the sound – or lack thereof – at the Collective Thread’s typically humming headquarters is a striking indicator of how much things have changed since the COVID-19 crisis became a reality for St. Louis. Just this January, Zaimi was settling into her new role as a floor manager in training at the fashion-focused nonprofit, having learned her craft through its sewing school only three months prior. Zaimi loved spending her days surrounded by buzzing sewing machines, friendly chatter amongst sewers and the general hustle and bustle of the business, all of which went quiet this March when the Collective Thread’s operations ground to a screeching halt due to the pandemic.

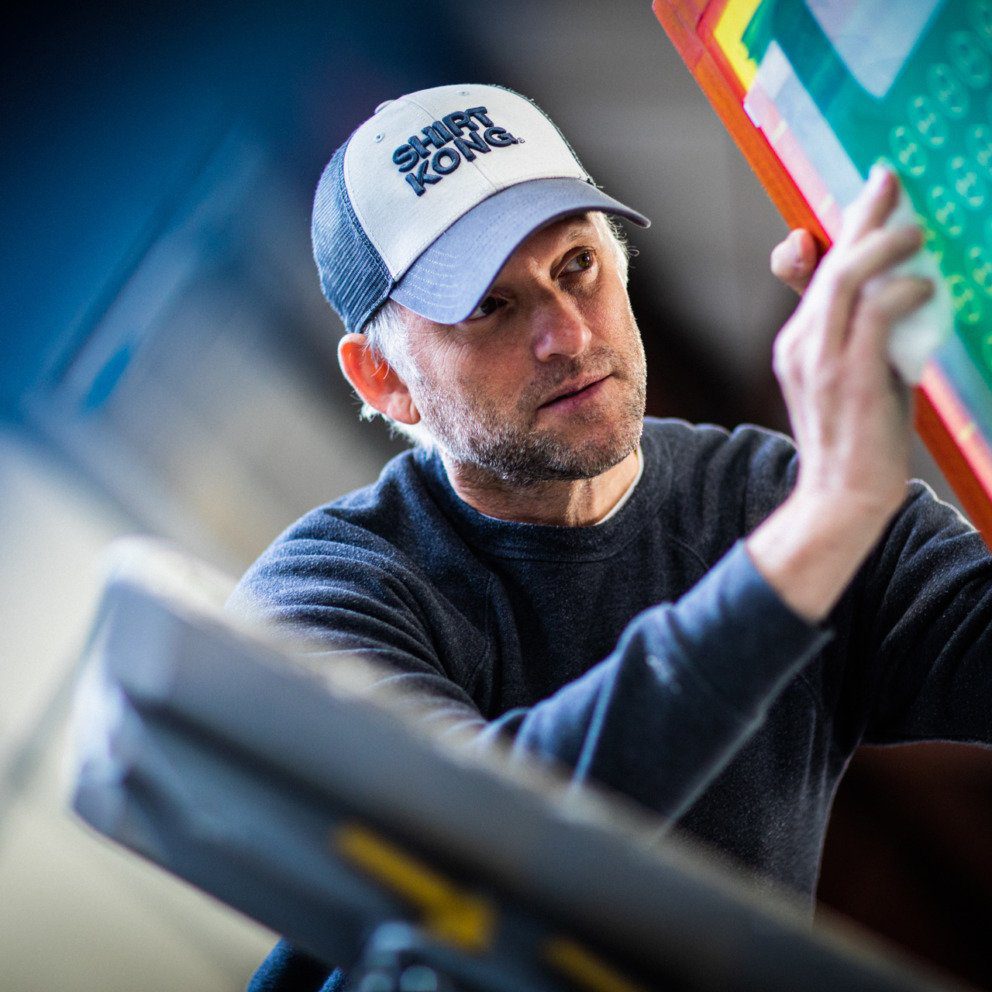

To Zaimi and her fellow sewers, the Collective Thread is more than a job with a unique soundtrack; it’s a lifeline that has helped them generate a sense of purpose and become part of a community. Co-founders Annie Miller and Terri Stipanovich had exactly this mission in mind when they started the Collective Thread last year. Their idea was to create an organization that would empower immigrant and refugee women by teaching them skills to fill the need in the city’s fashion scene for a full-service, cut-and-sew operation. Drawing on their collective experience – Miller’s 35-year career in the fashion industry, and Stipanovich’s decade-long work with refugees in East Africa – the pair joined forces and launched the Collective Thread last summer, using sewing as a way by which women like Zaimi can find meaningful work.

By this March, they were well on their way to realizing that vision. Their sewing school, a free program open to immigrant and refugee women in St. Louis, had graduated several classes of women – many of whom were hired on as sewers for their small-batch manufacturing operation. The organization had established itself in its new headquarters on Washington Avenue’s Fashion Row, purchased specialty equipment and was inundated with requests for its sewing and design services from companies like Summersalt and Tharpe. Then, everything changed.

“It was pretty devastating,” Stipanovich says. “We’re no different from anyone else even though we are a nonprofit. We have a reliance on the generated income from our small batch and design services, and immediately when COVID hit, everything came to a screeching halt. We could no longer hold classes. Our customers were being hit hard economically, so they had to put a hold on their projects. We were scheduled out for months with projects queued up, and everything just stopped.”

Miller and Stipanovich were scared, and not just about how they were going to pay rent and keep the lights on. Their main concern was for the Collective Thread’s sewers: Immigrant and refugee women who, as a vulnerable population, faced both economic and personal crisis should the Collective Thread go dark. Miller and Stipanovich knew they couldn’t let their mission fail when those it served needed them most so, after a week of sleepless nights and spinning their wheels trying to figure out what to do, they came up with a solution.

“We started hearing about masks,” Stipanovich says. “We knew there was a need, and since we are a full-service sewing operation, we knew we could do it.”

Miller and Stipanovich reached out to their supporters at the Lutheran Foundation of St. Louis and obtained a grant to help the Collective Thread get their mask-making operation up and running. In no time, Miller had developed a mask design based on information from health organizations, and she, Miller and Zaimi got to work creating materials kits and getting sewing machines to the Collective Thread sewers so they could work from their homes.

The mask program has been a tremendous success. Not only has the effort allowed given the Collective Thread a lifeline and allowed its sewers to earn income during the COVID-19 crisis, it’s been so successful that many of the women are making more money than they had before the pandemic. Between the 3,000 masks the Collective Thread has donated and the 8,000 orders from companies and individuals that it has sold, the Collective Thread has been so busy fulfilling orders that it’s had to hire on even more sewers to meet demand. They’ve even been able to provide special masks with clear panels in the front that allow the hearing impaired to read lips – something that Miller is especially proud of.

“Our whole why is to impact individual people’s lives, and during COVID, they are making more money than they were before COVID, which is really incredible – and they can work from home and have been super productive,” Stipanovich says. “We have one sewer whose husband would come and drop off 300-400 masks at a time and we asked, ‘Is she ok? Is she sleeping?’ It turns out he had lost his job and learned how to sew, so they’ve become this dynamic team. He told me they are going to finally be able to buy a house because of this.”

For Zaimi and her fellow sewers, though, the impact goes beyond the extra income. As the Collective Thread has given her and her colleagues the sense of purpose that a career can provide, it’s also made her want to give back in this time of crisis, not only to ensure that the organization’s important work can continue, but because she draws strength from working with others in her adopted community to help people in their time of need.

“In this period of COVID-19, I see a lot of people trying to help us make masks and donate fabric, so this is something good,” Zaimi says. “You feel that, in this period, there is always someone who can help. It’s a good feeling to feel that you are not alone in this situation. It feels human.”

Join the Story

- Need a mask? Consider buying from the Collective Thread.

- Don’t need a mask, but want to support the Collective Thread’s mission? Learn about the different ways you can donate.